The 8 Limbs of Yoga, as described in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, lay out a path that culminates in spiritual liberation. Asana, the practice of yoga postures, is where most modern yoga students start their journey, but it’s actually the third limb along the path. Pranayama (breath control) and deepening levels of meditation make up limbs four through eight.

Backtracking to the first two limbs brings us to yama and niyama, a code of ethics for interacting with the world and with oneself. Since the Yoga Sutras were likely written between 100 and 500 C.E., the context from which they emerged is wildly different from the ones in which they are now being taught, leaving plenty of room for debate and interpretation. Enter Stewart Gilchrist.

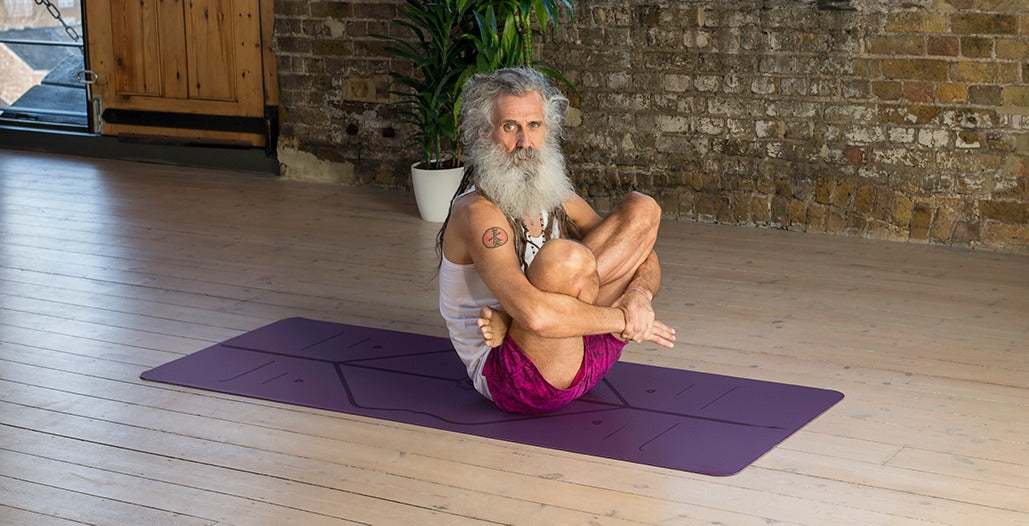

Stewart’s popular London yoga classes offer sweaty vinyasa with a healthy dose of philosophical discourse, so we were eager to get his take on how modern yoga students are connecting with the ancient eight-limbed path. It won’t surprise anyone who knows him that Stewart has questioned authority, upended tradition, and brought his own unique insights to the table.

What is the role of the 8 limbs of yoga for a modern yoga student?

Stewart Gilchrist: Whether a good thing or not, they have become pivotal and central to the teaching of modern yoga. A great majority of teachers and those running teacher trainings have given them a ubiquitous, central role in their teachings. They, therefore, have been established as the core of modern yoga teaching.

How do you incorporate teaching the 8 limbs into your classes?

SG: In many different ways: in studio classes, either as a focus for a whole month, in introduction to asana practice, during or after asana practice, in dedicated workshops, and in teacher trainings.

I live in London and teach over 300 people a week. They come from all over the world, from Jamaica to Japan, Norway to Nigeria. English is not always their first language. It is important that the philosophy of yoga is accessible in this environment.

It helps to make the limbs simple: ‘the don’ts’, ‘the dos’, posture, freeing the breath, letting go of the senses, focusing on one thing, praying, total integration. This may make them more comprehensible for all to follow.

With which aspects of the 8 limbs do you see modern students particularly struggle?

SG: All of them! The majority of people who come to my classes are only interested in asana. Those who start to want to deepen their knowledge tend to understand the Astanga [eight-limbed] yoga intellectually but struggle to practice them.

Any with which you yourself struggle?

SG: Aparigraha.

I do get incredibly attached to people; my children, friends, students, and to practice: teachers or those who inspire and have made an impression on me. I know that being so attached eventually leads to disappointment and dukha [suffering]! Non-attachment is a difficult practice.

Have you had any ‘aha moments’ around the 8 limbs that you could tell us about?

SG: They are not that important! Unless you need moral guidance. And even then most people just do not have the discipline or the will to apply any interpretation of them.

Would you discuss how you interpret the niyama ‘ishvara pranidhana’ [dedication to god]?

SG: Identify yourself with the source of all nature of all creation.

Differing religions may, therefore, be free to identify with their own personal gods while secularists and atheists can identify with their true nature. Try to be committed to that realisation. This tends not to alienate anyone from an interpretation.

What about brahmacharya [celibacy] for contemporary yogis who may be in relationships or have families?

SG: In the tradition of Patanjali, this meant abstinence. No sex. Like nuns and monks. However, other teachers, such as Krishnamacharya, proposed that the eight limbs can be practised by all in a system of Astanga yoga for householders, women, all castes, anyone!

I remember one of my teachers saying that brahmacharya means “good sex”! This always makes me laugh, as what is your definition of good sex? Others suggest “sexual responsibility” but what does this imply?

I am sure Bhagavan Rajneesh’s ideas on brahmacharya vary greatly from Mother Theresa May’s and this is simply how it will be: open to a wide range of definitions dependent on whoever’s principles you follow or have been indoctrinated with, or what you have developed yourself through experience.

Do you think the 8 limbs encourage yogis to be political activists?

SG: They should do. All those who follow the teachings of yoga should be political activists. My earliest recollection of yoga was in the sixties and yoga and hippy culture were vociferous in opposition to Vietnam, racism, apartheid, sexism, and the injustice of capitalism.

As the world veers toward a dystopian future with genocide in Africa, Syria, Yemen and countless other wars, it is frightening that the modern yogi is apathetic, to say the least, on political issues.

The environment, women’s rights, human rights, animal rights, homophobia, xenophobia, and social justice should all be on a yoga teacher’s agenda.